What’s a service mesh? And why do I need one?

Originally published by William Morgan on Buoyant.io.

tl;dr: A service mesh is a dedicated infrastructure layer for making service-to-service communication safe, fast, and reliable. If you’re building a cloud native application, you need a service mesh!

Over the past year, the service mesh has emerged as a critical component of the cloud native stack. High-traffic companies like Paypal, Lyft, Ticketmaster, and Credit Karma have all added a service mesh to their production applications, and this January, Linkerd, the open source service mesh for cloud native applications, became an official project of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation. But what is a service mesh, exactly? And why is it suddenly relevant?

In this article, I’ll define the service mesh and trace its lineage through shifts in application architectural over the past decade. I’ll distinguish the service mesh from the related, but distinct, concept of API gateways, edge proxies, and the enterprise service bus. Finally, I’ll describe where the service mesh is heading, and what to expect as this concept evolves alongside the cloud native adoption.

What is a service mesh?

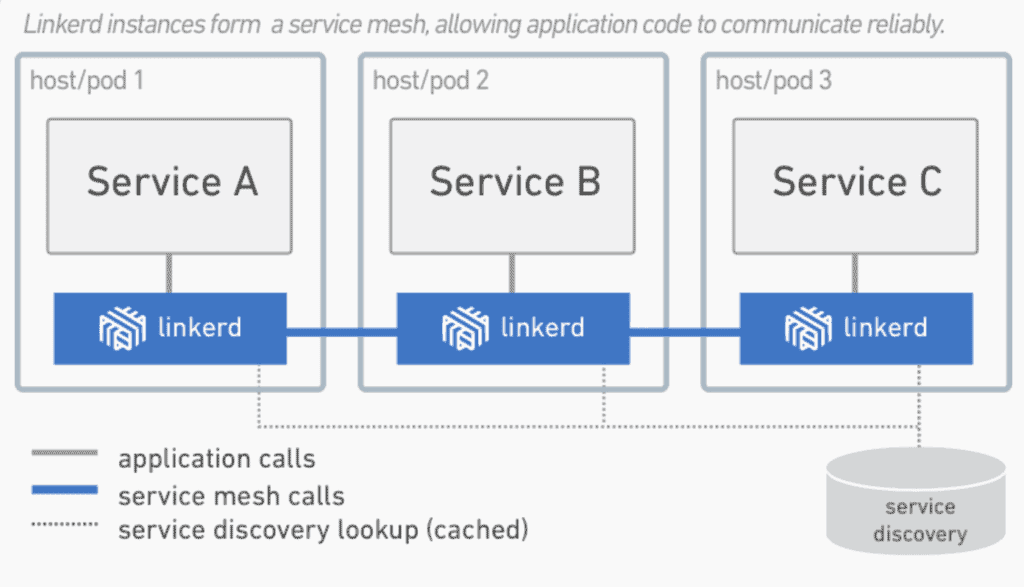

A service mesh is a dedicated infrastructure layer for handling service-to-service communication. It’s responsible for the reliable delivery of requests through the complex topology of services that comprise a modern, cloud native application. In practice, the service mesh is typically implemented as an array of lightweight network proxies that are deployed alongside application code, without the application needing to be aware. (But there are variations to this idea, as we’ll see.)

The concept of the service mesh as a separate layer is tied to the rise of the cloud native application. In the cloud native model, a single application might consist of hundreds of services; each service might have thousands of instances; and each of those instances might be in a constantly-changing state as they are dynamically scheduled an orchestrator like Kubernetes. Not only is service communication in this world incredibly complex, it’s a pervasive and fundamental part of runtime behavior. Managing it is vital to ensuring end-to-end performance and reliability.

Is the service mesh a networking model?

The service mesh is a networking model that sits at a layer of abstraction above TCP/IP. It assumes that the underlying L3/L4 network is present and capable of delivering bytes from point to point. (It also assumes that this network, as with every other aspect of the environment, is unreliable; the service mesh must therefore also be capable of handling network failures.)

In some ways, the service mesh is analogous to TCP/IP. Just as the TCP stack abstracts the mechanics of reliably delivering bytes between network endpoints, the service mesh abstracts the mechanics of reliably delivering requests between services. Like TCP, the service mesh doesn’t care about the actual payload or how it’s encoded. The application has a high-level goal (“send something from A to B”), and the job of the service mesh, like that of TCP, is to accomplish this goal while handling any failures along the way.

Unlike TCP, the service mesh has a significant goal beyond “just make it work”: it provides a uniform, application-wide point for introducing visibility and control into the application runtime. The explicit goal of the service mesh is to move service communication out of the realm of the invisible, implied infrastructure, and into the role of a first-class member of the ecosystem—where it can be monitored, managed and controlled.

What does a service mesh actually do?

Reliably delivering requests in a cloud native application can be incredibly complex. A service mesh like Linkerd manages this complexity with a wide array of powerful techniques: circuit-breaking, latency-aware load balancing, eventually consistent (“advisory”) service discovery, retries, and deadlines. These features must all work in conjunction, and the interactions between these features and the complex environment in which they operate can be quite subtle.

For example, when a request is made to a service through Linkerd, a very simplified timeline of events is as follows:

- Linkerd applies dynamic routing rules to determine which service the requester intended. Should the request be routed to a service in production or in staging? To a service in a local datacenter or one in the cloud? To the most recent version of a service that’s being tested or to an older one that’s been vetted in production? All of these routing rules are dynamically configurable, and can be applied both globally and for arbitrary slices of traffic.

- Having found the correct destination, Linkerd retrieves the corresponding pool of instances from the relevant service discovery endpoint, of which there may be several. If this information diverges from what Linkerd has observed in practice, Linkerd makes a decision about which source of information to trust.

- Linkerd chooses the instance most likely to return a fast response based on a variety of factors, including its observed latency for recent requests.

- Linkerd attempts to send the request to the instance, recording the latency and response type of the result.

- If the instance is down, unresponsive, or fails to process the request, Linkerd retries the request on another instance (but only if it knows the request is idempotent).

- If an instance is consistently returning errors, Linkerd evicts it from the load balancing pool, to be periodically retried later (for example, an instance may be undergoing a transient failure).

- If the deadline for the request has elapsed, Linkerd proactively fails the request rather than adding load with further retries.

- Linkerd captures every aspect of the above behavior in the form of metrics and distributed tracing, which are emitted to a centralized metrics system.

And that’s just the simplified version–Linkerd can also initiate and terminate TLS, perform protocol upgrades, dynamically shift traffic, and fail over between datacenters!

It’s important to note that these features are intended to provide both pointwise resilience and application-wide resilience. Large-scale distributed systems, no matter how they’re architected, have one defining characteristic: they provide many opportunities for small, localized failures to escalate into system-wide catastrophic failures. The service mesh must be designed to safeguard against these escalations by shedding load and failing fast when the underlying systems approach their limits.

Why is the service mesh necessary?

The service mesh is ultimately not an introduction of new functionality, but rather shift in where functionality is located. Web applications have always had to manage the complexity of service communication. The origins of the service mesh model can be traced in the evolution of these applications over the past decade and a half.

Consider the typical architecture of a medium-sized web application in the 2000’s: the three-tiered app. In this model, application logic, web serving logic, and storage logic are each a separate layer. The communication between layers, while complex, was limited in scope—there are only two hops, after all. There is no “mesh”, but there is communication logic between hops, handled within the code of each layer.

When this architectural approach was pushed to very high scale, it started to break. Companies like Google, Netflix, and Twitter, faced with massive traffic requirements, implemented what was effectively a predecessor of the cloud native approach: the application layer was split into many services (sometimes called “microservices”), and the tiers became a topology. In these systems, a generalized communication layer became suddenly relevant, but typically took the form of a “fat client” library—Twitter’s Finagle, Netflix’s Hysterix, and Google’s Stubby being cases in point.

In many ways, libraries like Finagle, Stubby, and Hysterix were the first service meshes. While they were specific to the details of their surrounding environment, and required the use of specific languages and frameworks, they were forms of dedicated infrastructure for managing service-to-service communication, and (in the case of the open source Finagle and Hysterix libraries) found use outside of their origin companies.

Fast forward to the modern cloud native application. The cloud native model combines the microservices approach of many small services with two additional factors: containers (e.g. Docker, which provide resource isolation and dependency management, and an orchestration layer (e.g. Kubernetes), which abstracts away the underlying hardware into a homogenous pool.

These three components allow applications with natural mechanisms for scaling under load and to handle the ever-present partial failures of the cloud environment. But with hundreds of services or thousands of services, and an orchestration layer that’s rescheduling instances from moment to moment, the path that a single request follows through the service topology can be incredibly complex, and since containers make it easy for each service to be written in a different language, the library approach is no longer feasible.

This combination of complexity and criticality motivates the need for a dedicated layer for service-to-service communication decoupled from application code and able to capture the highly dynamic nature of the underlying environment. This layer is the service mesh.

The future of the service mesh

While service mesh adoption in the cloud native ecosystem is growing rapidly, there is an extensive and exciting roadmap ahead still to be explored. The requirements for serverless computing (e.g. Amazon’s Lambda) fit directly into the service mesh’s model of naming and linking, and form a natural extension of its role in the cloud native ecosystem. The role of service identity and access policy are still very nascent in cloud native environments, and the service mesh is well poised to play a fundamental part of the story here. Finally, the service mesh, like TCP/IP before it, will continue to be pushed further into the underlying infrastructure. Just as Linkerd evolved from systems like Finagle, the current incarnation of the service as a separate, user-space proxy that must be explicitly added to a cloud native stack will also continue to evolve.

Conclusion

The service mesh is a critical component of the cloud native stack. A little more than one year from its launch, Linkerd is part of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation and has a thriving community of contributors and users. Adopters range from startups like Monzo, which is disrupting the UK banking industry, to high scale Internet companies like Paypal, Ticketmaster, and Credit Karma, to companies that have been in business for hundreds of years like Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

The Linkerd open source community of adopters and contributors are demonstrating the value of the service mesh model every day. We’re committed to building an amazing product and continuing to grow our incredible community. Join us!