Guest post by DatenLord

Summary

Anyone who has worked with async Rust has likely struggled with the bounds it requires, e.g., the ‘static bound on spawned tasks, MutexGuardcan not be held across .await point. Overcoming these constraints requires carefully structured scopes, which might result in opaque and nested code that is challenging for both the developer to write and for reviewers to read. In this talk, I will first list some pain points from my experience of writing async Rust code. Then, I will point out scenarios where we actually need async code and argue why we should separate async and non-async code. Finally, I will demonstrate how I’ve practiced this principle in a recent refactoring of Curp.

Pain Point

Spawned Task must be ‘static

The compiler has no idea how long an asynchronous task will run for when we create it; it may be ephemeral or it may continue to run until the program terminates. For this reason, the compiler requires all types owned by the tasks to be ‘static.

Such a limitation often leads to a lot of cloning before spawning a task. Admittedly, these codes help programmers to better understand which variables’ ownership should be transferred to the new task. Unfortunately, the code will look tedious.

let a_arc = Arc::clone(&a);

let b_arc = Arc::clone(&b);

tokio::spawn(async move {

// ...

});Non-Send variables cannot be held across .await point

The Tokio runtime can move a task between threads at every .await. That’s why all variables that are held across .await must be sent, bringing a lot of trouble when writing async functions.

For example, the following code does not compile because log_l, a non-Send MutexGuard, can not be held across the .await point.

let mut log_l = log.lock();

log_l.append(new_entry.clone());

broadcast(new_entry).await;As the broadcast could take a while, we don’t want the MutexGuard to be held across the.await point either. The compiler does a great job at pointing up places for possible performance improvement.

To avoid this, we naturally add a line to drop the lock just before broadcasting.

let mut log_l = log.lock();

log_l.append(new_entry.clone());

drop(log_l);

broadcast(new_entry).await;Sadly, it still won’t compile. The explanation here is from tokio official website:

The compiler currently calculates whether a future is Send based on scope information only. The compiler will hopefully be updated to support explicitly dropping it in the future, but for now, you must explicitly use a scope.

To get around, we must wrap our code in an redundant scope. The code is not elegant anymore🙁.

{

let mut log_w = log.write();

log_w.append(new_entry.clone());

}

broadcast(new_entry).await;More nested scope will be created if multiple locks must be acquired by an async function. When this happens, the code becomes unreadable and unmaintainable.

Side Note: You might be wondering why we don’t make use of the async lock(tokio::sync::Mutex) tokio offers. It can be held across the .awaitpoint and will save us a lot of trouble. That’s because it has relatively limited use cases in practice. Normally, we don’t want critical sections to be too long. For example, we don’t want to hold the lock when we are broadcasting the new entry. Therefore, be careful about async mutex, you don’t want to accidentally use it.

Async scenarios

The previously mentioned problems are, in my opinion, caused by a lack of clarity in the separation between async and non-async code. In other words, we may fail to separate the async part and non-async part when designing our application’s architecture. So, I will sort out the scenarios where we can actually take advantage of async Rust.

I/O

You don’t want I/O to block the current thread since I/O can take a long time. Async I/O helps us to hand out control flow to other tasks when we are waiting for I/O resources.

// .await will enable other scheduled tasks to progress

let mut file = File::create(“foo.txt”).await?;

file.write(b”some bytes”).await?;

Background tasks

You want to spawn a background task in order to handle things in the background(usually paired with the receive end of an async channel).

tokio::spawn(async move {

while let Some(job) = rx.recv().await {

// ...

}

};Concurrent tasks

You want to spawn multiple tasks to utilize multicore.

let chunks = data.chunks(data.len() / N_TASKS);

for chunk in chunks {

tokio::spawn(work_on(chunk));

}Wait for others

You want to pause the current thread and wait for some other events.

// wait for some event

event.listen().await;

// barrier

barrier.wait().await;As can be seen, async code usually resides in limited places: I/O, concurrent, and background tasks. Therefore, when we are designing our code, we can consciously identify async functions and try to minimize them. Separating these two parts can not only alleviate the pain points mentioned at the beginning of the article, but also help us to clarify the code structure.

// before

{

let mut log_w = log.write();

log_w.append(new_entry.clone());

// ...

}

broadcast(new_entry).await;

// after: move the logic to another function instead

fn update_log(log: &mut Log, new_entry: Entry) {

log.append(new_entry);

// ...

}

update_log(&mut log.write(), new_entry.clone());

broadcast(new_entry).await;Regarding a recent major refactor of Curp

Before refactoring, due to multiple iterations, the readability and structure of the code became increasingly poor. Specifically, we had several lock structures that needed to be shared among various parts of the Curp server, and most functions of Curp server were async. The async and locking code were mixed together, frequently leading to the aforementioned pain points during development.

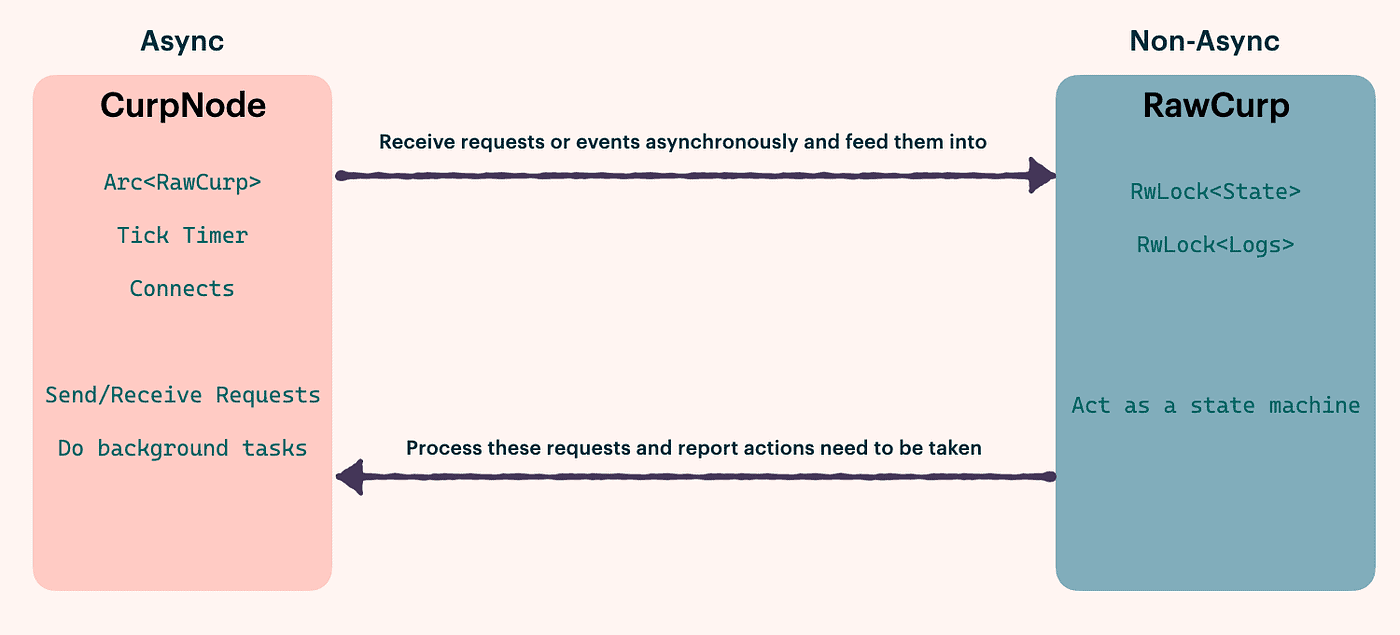

Therefore, we reorganized the structure of Curp server, dividing it into an async part called CurpNode and a non-async part called Rawcurp:

- CurpNode includes only async code

- I/O tasks: receiving, sending network requests, persisting log entries

- Background tasks: periodically checking leader activity, copying and aligning data on each node

- Rawcurp can be considered as a state machine that receives calls from CurpNode and updates the state. It includes only non-async code. If RawCurp wants to perform some async operations (such as broadcasting heartbeat), it can use return values and channels to let CurpNode make requests on its behalf.

Take our tick function as an example. Before refactoring, due to the limitation that LockGuard cannot pass the await point and the restriction of multiple logical branches, we had to organize the code in this way:

loop {

let _now = ticker.tick().await;

let task = {

let state_c = Arc::clone(&state);

let state_r = state.upgradable_read();

if state_r.is_leader() {

if state_r.needs_hb

{

let resps = bcast_heartbeats(connects.clone(), state_r, rpc_timeout);

Either::Left(handle_heartbeat_responses(

resps,

state_c,

Arc::clone(&timeout),

))

} else {

continue;

}

} else {

let mut state_w = RwLockUgradableReadGuard::upgrade(state_r);

// ...

let resps = bcast_votes(connects.clone(), state_r, rpc_timeout);

Either::Right(handle_vote_responses(resps, state_c))

}

};

task.await;

}After the refactoring, the code is significantly more understandable because all of the non-async functionality has been transferred to RawCurp.

loop {

let _now = ticker.tick().await;

let action = raw_curp.tick();

match action {

TickAction::Heartbeat(hbs) => {

Self::bcast_heartbeats(Arc::clone(&raw_curp), &connects, hbs).await;

}

TickAction::Votes(votes) => {

Self::bcast_votes(Arc::clone(&raw_curp), &connects, votes).await;

}

TickAction::Nothing => {}

}

}