Guest post by Tian Ye of DatenLord

The purpose of this article is to provide readers who have not been exposed to formal methods with a new perspective on computer systems and algorithms, rather than formal methods or TLA+ tutorials. Therefore, the focus of this article is how to think about programs from a mathematical perspective, without using a lot of space to explain the syntax of TLA+.

How do we write correct programs?

The goal of programming is always to write correct programs. Our programs become more complex over time, and the errors that may exist in them become more numerous. To write correct programs, we should first understand what errors may occur in our programs.

What errors will there be in the program?

I will roughly divide the errors that may occur in the program into two categories: simple errors and logical errors.

Simple errors

Simple errors include semantic errors, memory errors, etc. For these easy-to-analyze errors, we already have many mature methods and tools to avoid them, such as compilers, static analysis tools, garbage collector. Because these errors can be relatively easily found and fixed, they are not the focus of our attention.

Logical errors

Logical errors are the most difficult to find and fix in programs, such as deadlocks, race conditions, data inconsistencies. Logical errors affect the correctness, performance and reliability of the program, and are usually caused by insufficient design of the program. For these errors, we need to analyze and solve them from a higher level, rather than just from the implementation details of the code.

We usually use some methods to avoid logical errors, such as:

- Optimize software architecture design — Consider the correctness of the program in the design stage

- Testing — Use various testing methods to reduce the errors in the program, but it cannot guarantee the complete correctness of the program

Experience

It is not hard to see that the theories above are derived from experience. Experience is accumulated in practice, and we summarize the experience to derive guiding principles, methods and steps that can help us design better programs.

But can we rely only on experience?

The more experienced people are, the more details and possibilities they can think of, and the systems they design are usually more stable. But we can’t just rely on experience:

- Experience is limited — Human experience is limited and unreliable

- The behavior and state of complex systems are numerous — A complex system has too many behaviors and states to predict

- The requirements for correctness of a specific program are very high — Some programs have very high requirements for correctness, such as financial systems, medical systems, which are difficult to guarantee through experience

- Unable to verify correctness from theory — Can only reduce the occurrence of errors as much as possible, but cannot prove the correctness of the program from theory

Therefore, we need a more rigorous method to guarantee the correctness of the program from the design.

Formal methods

If we can verify the correctness of a program from mathematical perspective, we can solve the above problems. Actually, this is the goal of formal methods.

Formal methods are based on mathematics, by establishing mathematical models for systems to define the behavior, state, etc. of the system, and then defining the constraints of the system, such as safety, liveness, and finally proving that the model satisfies the formal specification of the system to verify the correctness of the system. For finite-state systems, model checking based on finite-state search can be used to verify the behavior of the system to verify whether the system has the expected properties. For systems with infinite state spaces, deductive verification based on logical inference is used to verify the correctness of the system using induction.

This article uses the TLA+ language as a tool to introduce formal methods.

TLA+

Leslie Lamport, the author of TLA+, is a computer scientist who won the Turing Award in 2013 for his groundbreaking work in the field of concurrent and distributed systems.

What is TLA+?

TLA+ is an high-level language for modeling programs and systems — especially concurrent and distributed programs and systems. Its core idea is that the best way to precisely describe things is to use simple mathematics. TLA+ and its tools can be used to eliminate design errors that are difficult to find and correct in code and are expensive to correct.

TLA+ specifications are not real engineering code and cannot be used in production environments because the goal of TLA+ is to find and solve logical errors at the design stage of the system. In TLA+ we abstract programs as finite-state mathematical models, usually state machines, and then use the TLC Model Checker to exhaustively search all possible states of the program and verify its correctness.

The following two simple examples introduce TLA+. These two examples are from Leslie Lamport’s The TLA+ Video Course. The goal of this article is to provide a new perspective on computer systems and algorithms for readers who have not been exposed to formal methods, rather than a TLA+ tutorial, so the syntax and use of TLA+ tools will not be discussed in detail.

Simple Example

TLA+ allows us to use simple mathematics to abstract system models, mainly set theory and boolean logic. In the process of abstraction, we need to abandon some implementation details and only focus on the logic of the program itself.

Here is a simple C program that we try to abstract as a TLA+ program:

int i;

void main() {

i = someNumber(); // someNumber() returns a number between 0 and 1000

i = i + 1;

}State Abstraction

We need to abstract this program into a series of independent states. Obviously, the difference between each state is only the value of i. Suppose that the default value of i is 0 after initialization, and that someNumber()returns 42 when this program is run, then the state transition relationship of this program is:

[i : 0] -> [i : 42] -> [i : 43]There are three states in this, and the difference between each state is that the value of i is different.

It seems that the abstraction is complete, but there are problems. Suppose that someNumber() returns 43 in another run, then the state transition relationship of this program is:

[i : 0] -> [i : 43] -> [i : 44]This is inconsistent with the previous abstraction, because the state transition relationship of the two runs is different. This is because we have not considered the return value of someNumber().

The state of a program refers to the time point when the program is at each stage, not the process of the program running. Therefore, each state is independent, and the transition between states is atomic. This is very different from traditional programming, which is procedural, and TLA+ is state-oriented. We only care about what state the program is currently running in, so we can introduce a new variable pc to represent which stage the program is running in, so that we can clearly represent the sub-state relationship of the program:

int i;

void main() {

i = someNumber(); // pc = "start"

i = i + 1; // pc = "middle"

} // pc = "done"In this way, we no longer need to consider the value of i, but only the value of pc:

[pc : start] -> [pc : middle] -> [pc : done]Writing States

The initial value of i is 0, and the initial value of pc is start, so we can write the sub-state relationship as:

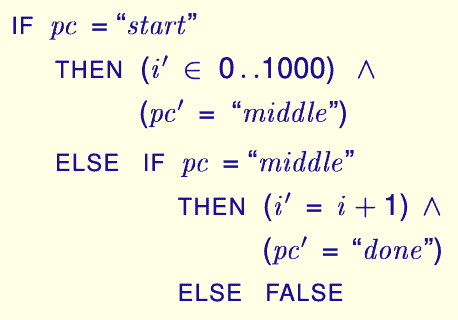

In which, for the variable i, its next state is represented as i’, which is the way TLA+ defines the state transition of variables. i’ ∈ 0..1000 means that the value of i in the next state is a number between 0 and 1000, that is, someNumber(), 0..1000 represents the set {0,1,…,1000}. ∧ is the logical and in Boolean logic, which can be understood as “and”. Finally, the program runs to completion and there is no next state, so it is represented as FALSE.

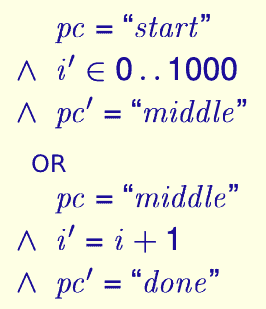

In TLA+ , we write a state. Therefore, it is not “because pc = start so i’ ∈ 0..1000″, in fact, the relationship between the two is parallel: In this state, the value of pc is start and the value of i in the next state ∈ 0..1000. With this idea, we can rewrite the above abstraction as:

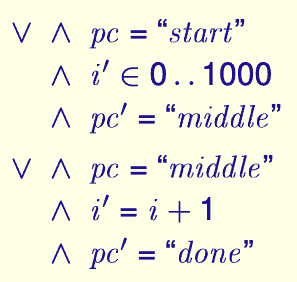

In which, the “or” is used to connect two states, which can be represented by the logical or ∨ in Boolean logic. In this way, we can clearly represent the state transition relationship of the program. For the sake of beauty, the same Boolean logic symbol can also be supplemented before the first sentence in TLA+ :

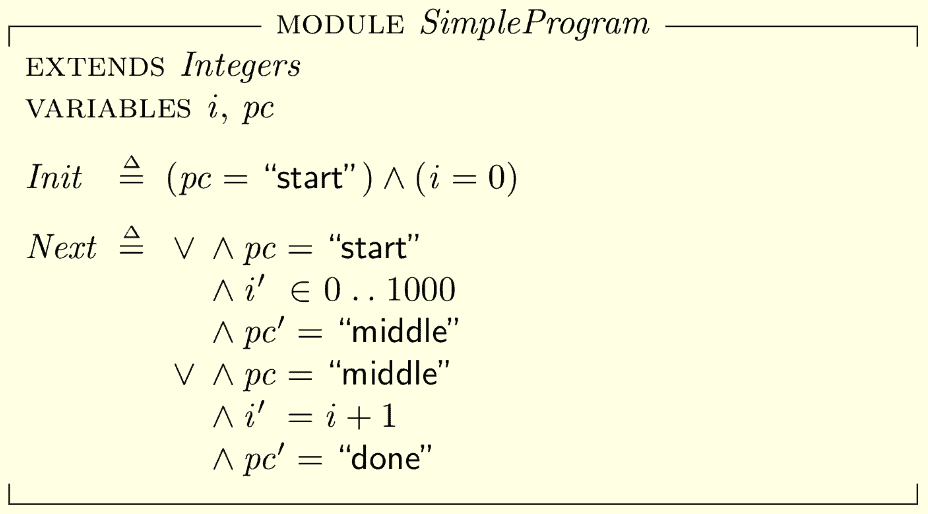

We finally get the two states after the initial state of this simple program, and then we will complete the initial state and supplement the entire specification according to the requirements of the TLA+ language:

- EXTENDS is used to introduce modules defined in other specifications, which is mainly used in i’ ∈ 0..1000 here.

- VARIABLES is used to define variables, which are defined as i and pchere.

- Init is used to define the initial state, which is defined as i = 0 and pc = “start” here.

- Next is used to define the state transition relationship.

Now we have a complete TLA+ specification. Later, we can use the TLC Model Checker to check the model, but this is not within the scope of this article.

For simple systems, modeling with TLA+ cannot bring many benefits. Generally speaking, TLA+ is only used when designing very complex, very critical, and very experience-based systems. Concurrency and distributed systems are usually the fields where TLA+ is used. Let’s take a look at an example of a distributed system algorithm: Two-Phase Commit.

Two-Phase Commit

In transaction processing, databases, and computer networking, the two-phase commit protocol (2PC) is a type of atomic commitment protocol (ACP). It is a distributed algorithm that coordinates all the processes that participate in a distributed atomic transaction on whether to commit or abort (roll back) the transaction. This protocol (a specialised type of consensus protocol) achieves its goal even in many cases of temporary system failure (involving either process, network node, communication, etc. failures), and is thus widely used. — — Two-phase commit protocol (Wikipedia)

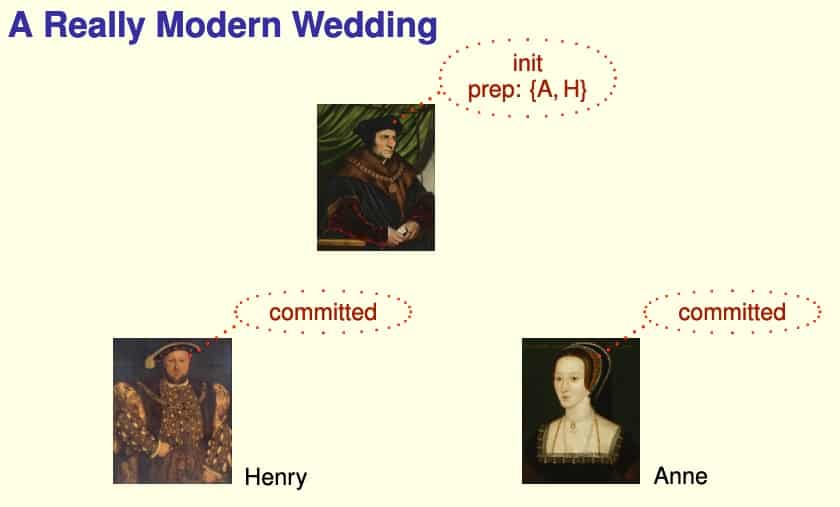

Lamport explains Two-Phase Commit in the following analogy in Leslie Lamport’s The TLA+ Video Course:

In a wedding, the minister is the coordinator, the groom and the bride are the participants. When the groom and the bride both agree to the marriage, the minister will officially announce the marriage. If one of them does not agree, the minister will abort the marriage:

- The minister asks the groom: Do you agree to this marriage?

- The groom answers: I agree (prepared).

- The minister asks the bride: Do you agree to this marriage?

- The bride answers: I agree (prepared).

- The minister announces: The marriage is officially established (committed).

If one of them does not agree, the minister will abort the marriage.

In a database, the Transaction Manager is the coordinator (the minister). When the Transaction Manager asks all the participants Resource Managers (the groom / bride), if all the Resource Managers agree to commit the transaction, the Transaction Manager will commit the transaction. If one of them does not agree, the Transaction Manager will abort the transaction.

The detailed introduction and process of Two-Phase Commit can be found on Wikipedia.

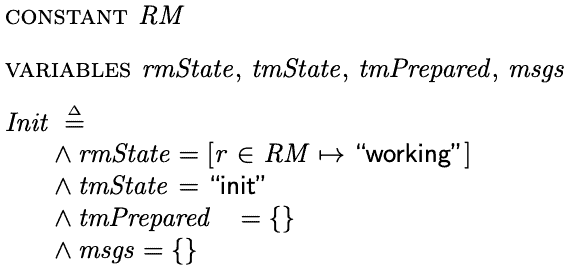

First, let’s define some constants and variables and their initial state:

- The constant RM is the set of all Resource Manager identifiers, for example, it can be set to the set {“r1”, “r2”, “r3”}.

- The variable rmState is used to record the state of each Resource Manager, and rmState[r] is used to represent the state of r, which has four states: working, prepared, committed, aborted. The initial state of each RM is working.

- The variable tmState is used to record the state of the Transaction Manager, which has three states: init, committed, aborted. The initial state is init.

- The variable tmPrepared is used to record the Resource Manager that is ready (in the prepared state). The initial value is an empty set.

- The variable msgs is used as a message pool to record all messages that are being transmitted. The initial value is an empty set.

Next, let’s define the actions that the system may perform.

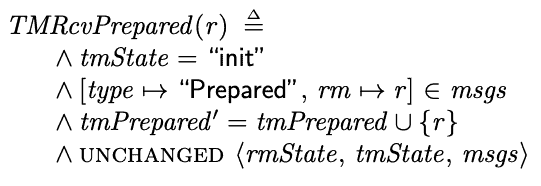

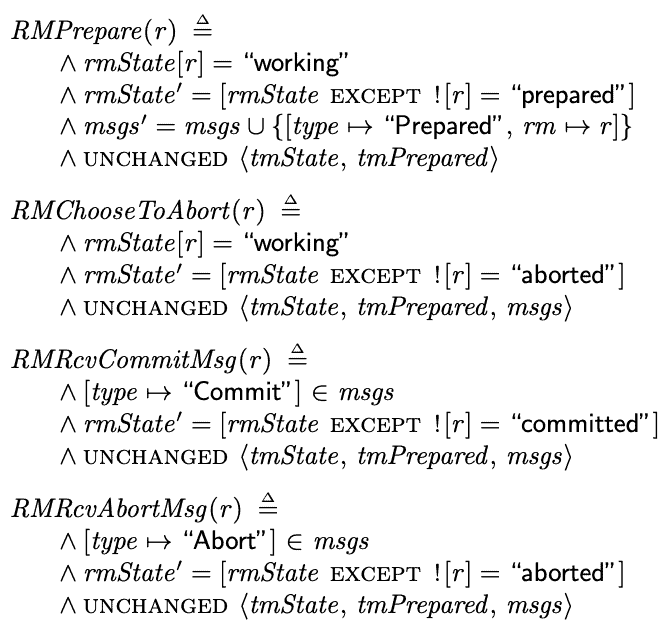

- In TLA+, expressions similar to the “function” concept in other programming languages can be defined in the above way, so there is no need to define an expression for each Resource Manager.

- [type → “prepare”, rm → r] is a record in TLA+, similar to a struct in other programming languages.

- UNCHANGED ⟨rmState, tmState, msgs⟩ means that this action will not change the values of the variables rmState, tmState, msgs. In TLA+, it is necessary to explicitly declare whether the value of each variable changes or not.

When the state of TM is init, and there is a Prepared message from r in the message pool, the value of tmPrepared in the next state will be the union of tmPrepared and {r}.

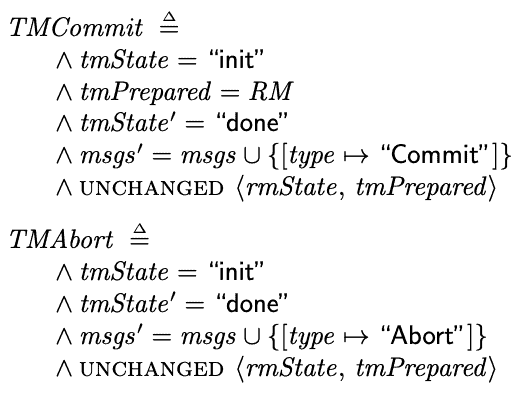

The above two actions are Transaction Manager performing Commit and Abort.

The above 4 Resource Manager actions are Resource Manager choosing Prepare and Abort, and handling the Commit and Abort decided by the Transaction Manager.

The syntax rmState’ = [rmState except ![r] = “prepared”] means “in the next state, the value of rmState[r] is changed to prepared, and the other parts remain unchanged”.

If we use a form like rmState[r]’ = “prepared”, we have not explicitly stated the values of the other parts of rmState in the next state, so it is incorrect.

TLA+ is different from the programs we usually write, it is mathematics. In programming, we use arrays, and in TLA+, we use functions to express similar concepts, and the set of array indices is the domain of the function.

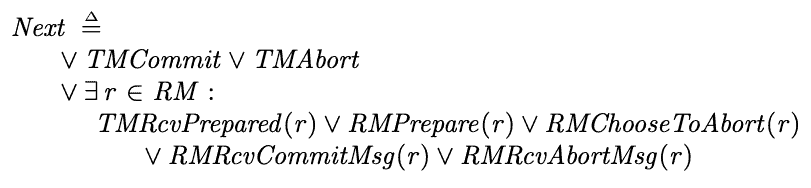

After writing all the actions that the system may exist, we can start to deduce the state transition of the system:

We use the existential quantifier ∃r ∈ RM to represent “for any element r in the set RM, there is such an action”. The state transition in TLA+ is atomic, so in a state, only one r will be selected in this “or” branch, which can be compared to the for r in RM in the programming language, but fundamentally different.

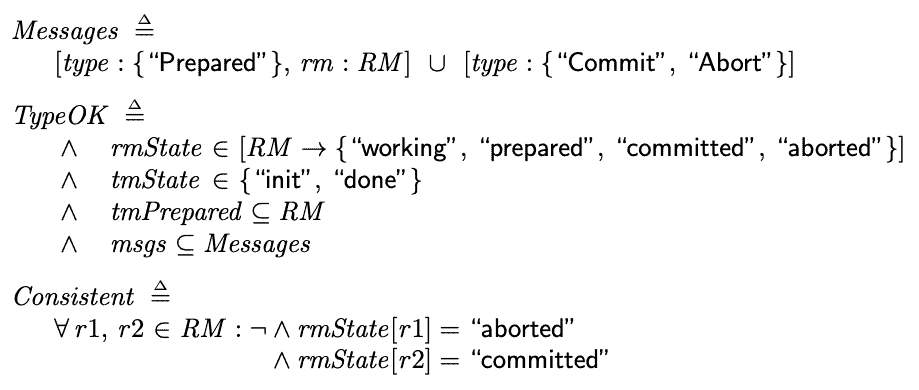

At this point, the modeling of the system is complete. Now we need to write the system’s constraint conditions:

In the constraint condition TypeOK, we have limited the possible values of each variable. The [RM → {“working”, “prepared”, “committed”, “aborted”}] is similar to the Cartesian product of the set RM and the set {“working”, “prepared”, “committed”, “aborted”}, but the result is a set composed of records:

{

[r1 |-> "working", r2 |-> "working"],

[r1 |-> "working", r2 |-> "prepared"],

[r1 |-> "working", r2 |-> "committed"],

...

[r1 |-> "aborted", r2 |-> "committed"],

[r1 |-> "aborted", r2 |-> "aborted"]

}In TypeOK, we use the set Messages defined above. When defining Messages, we used the syntax: [type: {“Prepared”}, rm: RM]. This syntax is also similar to the Cartesian product of {“Prepared”} and RM, but the result is also a record set:

{

[type |-> "Prepared", rm |-> r1],

[type |-> "Prepared", rm |-> r2],

...

}The final constraint condition Consistent is used to ensure the consistency of the system: at any time, it is impossible for two Resource Managers to be in the committed and abort state respectively.

Finally, we will give the constraint conditions as invariants, together with the system model, to the TLC Model Checker for verification, and we can prove the correctness of the system.

Summary

From the above two examples, we have a preliminary understanding of the idea of formal methods. TLA+ is designed for verifying distributed systems, but its ideas can be applied to fields far beyond distributed systems. When writing programs, if we can not only consider the contents on the code level, but also think from a higher level, from a mathematical point of view, we can write morewe robust programs.

If you are interested in TLA+, you can refer to Leslie Lamport’s The TLA+ Video Course — YouTube and Learn TLA+.

Xline

TLA+ is widely used in the research and development of distributed system algorithms. In our project Xline, TLA+ is used to verify the correctness of the consensus algorithm during the design phase. Xline is a geo-distributed KV store for metadata management. We are using a modified version of [Consistent Unordered Replication Protocol (CURP)](https://www.usenix.org/system/files/nsdi19-park.pdf) as the consensus protocol in Xline, and TLA+ is used to guarantee the correctness of it in our design.

If you are looking for more information about our project Xline, please refer to our Github: https://github.com/datenlord/Xline